With the exception of the occasional James Bond movie that proves the rule, we don’t as a matter of course combine our modes of transportation into one all-purpose vehicle, and we even tend to park our cars, boats and planes in separate facilities. But when it comes to financial management, there is apparently this one-size-fits-all tool commonly called the Budget that we apply to all problems involving dollar signs.

Before we get into the details of exactly how bad of an idea this actually is, a little structure to this discourse would be beneficial, that structure coming in the form of a three-tier hierarchy for financial management.

At the top level resides Strategy and the Forecast, or rather, Forecasts, plural, as the enterprise seeks to gain as much information, insight and foresight from as many sources and time horizons as seem reasonable, such as 60-day cash collection forecasts from A/R, 90-day Ops forecasts from ERP, six-month sales forecasts from the field, 9-month staffing and expense forecasts from the functional departments, 1-year product launch forecasts from marketing, and 2-year industry outlooks from the analysts.

At the top level resides Strategy and the Forecast, or rather, Forecasts, plural, as the enterprise seeks to gain as much information, insight and foresight from as many sources and time horizons as seem reasonable, such as 60-day cash collection forecasts from A/R, 90-day Ops forecasts from ERP, six-month sales forecasts from the field, 9-month staffing and expense forecasts from the functional departments, 1-year product launch forecasts from marketing, and 2-year industry outlooks from the analysts.

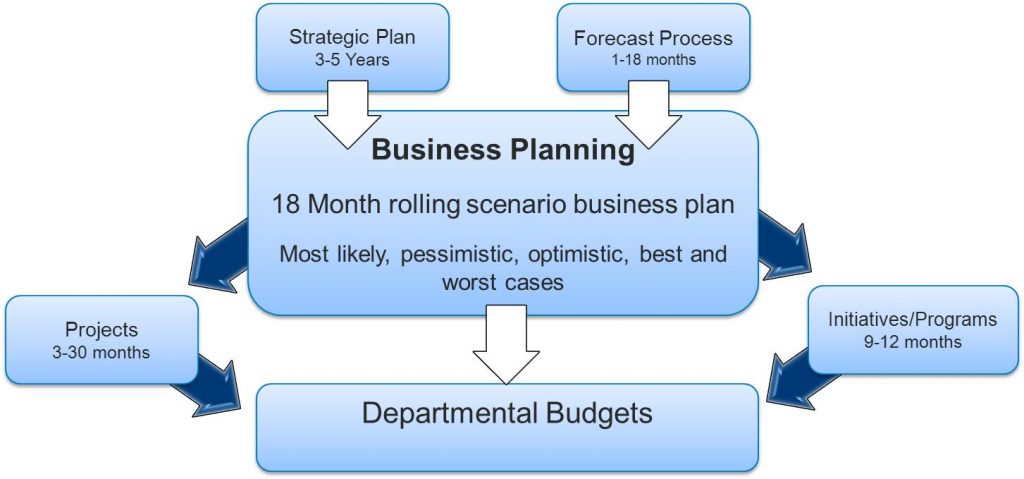

At the bottom is of course the Budget, the intended output of the whole process. Between these two levels lives the most neglected and under-resourced activity in finance – Planning. Too often we connect the budget directly to the forecast, resulting in after-the-fact knee-jerk responses and half-way measures such as hiring freezes, salary freezes, capital freezes and travel freezes that please no one, not even the CFO who issues them. Or, when the Budget gets too far out of line during the middle of the year, we confound the situation by substituting Variance-to-Budget with Variance-to-Forecast, which merely moves the game playing from the budget to the forecast, a much, much more detrimental location for gaming than if it could be restricted to the budget. You do NOT want your forecast process tied to performance; assuming that the definition of a Forecast is “what you think will happen” (see below), you want the most accurate picture, the best guesses, put forward, unfiltered and unaffected by how that might affect year-end bonuses. What should drive the Budget are the Scenarios that result from the planning process; not just the Most-Likely Case, but also the Optimistic, Pessimistic, Best and Worst cases as well.

To drive this point a little further, consider these definitions that Steve Player shared with us at this week’s ABM Smart conference in Charlotte:

- TARGETS: What you’d like to happen

- FORECAST: What you think will happen

- PLANS: What you intend to do

When it comes to the definition of the BUDGET, however, it gets a little messier, as it seems we tend to apply a James Bond approach to this tool. Here is just a partial list of what many organizations use the Budget for: Cash planning, Targets and incentives, Investments, Cost understanding, and Resource management. I will submit to you that the use of the Budget should be limited to that last item – Resource management and allocation, and reallocation, and reallocation, as conditions change, which they always do, and not always in neat 12-month segments aligned with the Gregorian calendar.

The first usage you want to decouple from the Budget are Targets and incentives. You cannot be an agile organization, reacting quickly to opportunities and challenges, if in order to implement a revised budget you must also renegotiate the associated bonus schemes at all levels across the organization. Targets and incentives are best managed through the use of a Balanced Scorecard, where they can be tied to inter-related key metrics and to external benchmarks such as growth and market share that better reflect the health and performance of the organization than an internal, departmental budget.

Investment decisions do not naturally reside comfortably at the level of the budget; they are most at home at the intersection of Strategy and Planning. Variances-to-Budget do nothing to improve your understanding of Costs, as they assume what remains to be proven – what SHOULD the costs be. For that you need an understanding of the processes and activities which consume the resources, and the ability to benchmark them with best-in-class players in your industry. As for Cash, we all know that cash ends up being the “plug” that makes the balance-sheet balance, and that every organization relies on a more rigorous treasury process to assure adequate supplies of working capital.

So what’s the Budget for? Resource Allocation. And reallocation. And reallocation. So unless you are in fact James Bond, for everything else, employ a purpose-built performance management vehicle.

3 Comments

Pingback: Consolidator? Or Consolidatee? - Value Alley

Pingback: Stop Reporting Variances, Start Impacting Results - Value Alley

Pingback: Rolling forecasts, or Who ordered that? - Value Alley